1. What does the word impressment mean in regards to the War of 1812?

The bodily causes of the War of 1812 are difficult to make up one's mind, in part because much of the war-time propaganda obscured the truthful causes.

That being said, most historians don't believe in that location was a single cause but rather a variety of causes, some of which were official while others were unofficial.

The official causes were originally listed in a bulletin that President James Madison sent to Congress on June 1, 1812, in which he listed complaints about British behavior toward America.

According to an commodity by the Function of the Historian on the U.Southward. Department of State's website, the truthful causes are varied but are evident in the treaty that ended the war, the Treaty of Ghent, which was signed in 1814:

"On Christmas Eve British and American negotiators signed the Treaty of Ghent, restoring the political boundaries on the North American continent to the status quo ante bellum, establishing a boundary commission to resolve further territorial disputes, and creating peace with Indian nations on the frontier. Equally the Ghent negotiations suggested, the existent causes of the state of war of 1812, were not merely commerce and neutral rights, but also western expansion, relations with American Indians, and territorial control of North America."

The following is a list and explanation of the possible causes of the War of 1812:

These complaints were:

Impressment of American sailors.

Continual harassment of American commerce by British warships.

British laws, known as Orders in Council, declaring blockades against American ships bound for European ports.

Attacks past Native-Americans on American frontiers believed to be instigated past British troops in Canada.

The unofficial causes were never mentioned publicly and instead have been pieced together by historians over the years.

The following is a listing of the possible causes of the War of 1812:

Impressment:

Impressment is the act of forcing men into military service. Britain had a long history of using impressment but escalated this practice after the Napoleonic Wars began in 1803.

Betwixt 1803 – 1812, the British Navy reportedly captured between 5,000 – 9,000 American sailors at sea and "pressed" them into their navy as a way to deal with manpower shortages (Borneman twenty.)

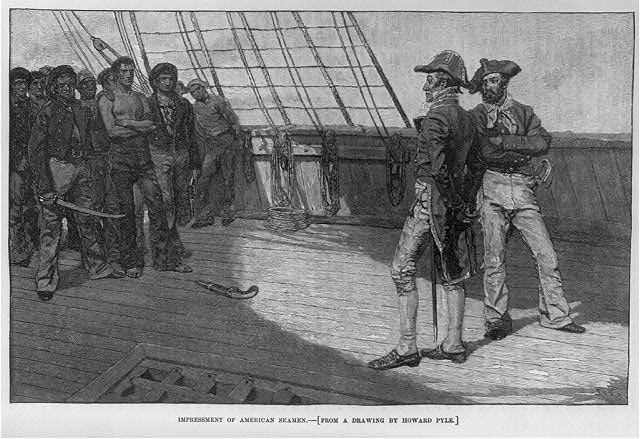

Impressment of American seamen, analogy published in Harper'southward Monthly Magazine, circa 1884

The issue of impressment caused a public outrage in America and is believed to exist one of the chief causes of the State of war of 1812.

Impressment became a popular issue in the press before it even appeared on President James Madison's list of grievances against Britain in his June i, 1812 message to Congress.

Yet, some historians at present question how much of a factor impressement actually was in the build up to the war. According to an article past John P. Deeben on the National Archives website, out of the total population of iii.ix to seven.2 million Americans, the impressment of fewer than 10,000 Americans between 1789 and 1815 was rather insignificant.

Furthermore, Americans sometimes good impressment themselves, such as the case with British seamen Charles Davis who was captured and forced to serve aboard the USS Constitution in 1811. (Deeben par 3.)

Co-ordinate to Denver Brunsman in his volume The Evil Necessity, whether impressment was the cause of the War of 1812 or not, it definitely became the justification for it:

"American historians have argued for generations about the causes of the War of 1812, from impressment and the Orders in Council to American expansionist desires and the rivalry betwixt Republican and Federalist parties. One signal is irrefutable: Impressment served every bit the key justification for the war once it began. On June 23, 1812, the British government repealed the Orders in Quango without knowing (because of normal delays in transatlantic communication) that the United States had declared war on Britain five days before. Thereafter, America'south only remaining condition for peace was that Britain concord to stop impressing from American merchant ships."

Republican politicians of the time oft compared impressed American sailors to white slaves as a manner to evoke strong public reactions. In fact, on Nov 29, 1811, the House Strange Relations Commission report charged that Britain "enslaves our seamen."

When the argument that British Orders in Council were infringing on American trade rights failed to ignite the public's anger in the build up to the state of war, politicians began to lean even more than heavily on the impressment issue.

British Orders-In-Council:

The Orders In Council in Bang-up Britain were a series of Parliamentary Acts intended to proceeds control of the neutral merchant shipping merchandise with Europe during the 18th and 19th centuries.

When the Napoleonic Wars broke out between France and Great britain in 1803, both sides tried to prevent neutral countries, such as the United States, from trading with the other in an effort to deprive their opponent of supplies.

On January 7, 1807, Britain issued the following Society in Council:

". . . it is hereby ordered, that no vessel shall exist permitted to trade from i port to another, both which ports shall belong to, or be in the possession of France or her allies, or shall be then far under their control as that British vessels may not freely merchandise thereat; and the commanders of his majesty's ships of war and privateers shall be, and are hereby instructed to warn every neutral vessel coming from any such port, and destined to some other such port, to discontinue her voyage, and non to proceed to whatsoever such port; and any vessel, subsequently beingness so warned, or any vessel coming from whatsoever such port after a reasonable time shall have been afforded for receiving information of this his majesty's orders which shall be found proceeding to another such port, shall exist captured and brought in, and together with her cargo, shall be condemned as lawful prize."

This prescript prohibited neutral ships from carrying goods betwixt ports within Napoleon'due south empire and declared that the Majestic Navy would board any ship suspected of carrying goods to French ports and confiscate the contents to sell as prizes of state of war. The prescript stated that any nation wishing to trade with closed ports must first pay transit duties.

This was followed by a second edict issued on Nov 11, 1807, which banned all neutral trade with any port on the European continent.

On December 17, 1807, Napoleon responded with the Milan Decree, which alleged that the French navy would capture all ships trading with Keen U.k. or its colonies and confiscate their goods.

The British Orders In Council are considered 1 of the many causes of the War of 1812 and were listed on Madison'southward list of grievances to Congress in 1812.

Still some historians, such as Alan Taylor, incertitude the orders in council were a factor at all in the proclamation of state of war.

Alan Taylor argues in his book, The Civil War of 1812, that if the orders in council were the cause, there would take been an easy solution to the problem:

"Moreover, if the orders had been the sole and pressing cause for declaring war, the disharmonize would accept been brief. On June xvi, 1812, only before the Americans declared war, the British suspended the Orders in Quango. They acted to better a depressed economy in Britain and to avoid a costly state of war with America. Hastening the news by send across the Atlantic to America, the British expected the Madison administration promptly to restore peace, as information technology would have washed had the orders truly been the sole major cause of the war. But Madison and the Republican Congress fought on, citing impressed sailors and attacking Indians as enduring grievances" (Taylor 134.)

Taylor goes on to explain that politicians at get-go tried to use the Orders in Council every bit a way to pulsate up support for the war just the public was indifferent to the issue:

"At first, in November of 1811, the president and Congress did emphasize the British Orders in Quango as a justification of state of war. But the complicated issues of maritime restrictions did not suffice to stir the common Americans needed to win elections, man privateers, and serve in the ground forces. Every bit the push for war intensified, Republicans turned up the rhetorical heat by emphasizing impressment as a primary grievance. Beginning in Feb, the nation'south nigh influential paper, the Aurora, devoted far more space to impressment than to the Orders in Council…Impressment also loomed big in Madison's address of June 1, 1812, and larger still in the response by Calhoun and the House of Strange Relations Committee" (Taylor 135.)

As the Orders in Quango failed to ignite public outrage in the build up to the war, it became less of a focal indicate for Republican politicians and they instead started to focus their efforts on other issues like impressment.

Indian Attacks Instigated by the British in Canada:

A common complaint against the British at the time was that they were supplying Indian tribes of the Ohio Valley and the Swell Lakes with weapons and were instigating Indian attacks against American settlements, according to an article on the American Battleground Trust website:

"The British, eager to slow the The states' rise, supported an 'Indian State' effectually the Bully Lakes to cheque American expansion and create a buffer for British Canada. Fur trade in the region was booming, giving the British added incentive to cooperate with the Native Americans. To facilitate this, the British occasionally provided the Native tribes with arms and supplies. These minor provisions were exaggerated, in plough, by indignant and worried Americans. Continued British involvement was seen every bit an affront to American sovereignty."

To that avail, some politicians, such as Thomas Jefferson, argued that conquering Canada and expelling the British from the American frontier was the only way to end these Indian attacks, co-ordinate to Taylor:

"To render the war popular, Jefferson advised Madison that he needed, to a higher place all, 'to end Indian barbarities. The conquest of Canada will practise this.'" (Taylor 137.)

In reality, many historians believe the claims of Indian attacks being instigated by the British were exaggerated and were just an excuse to conquer and annex Canada.

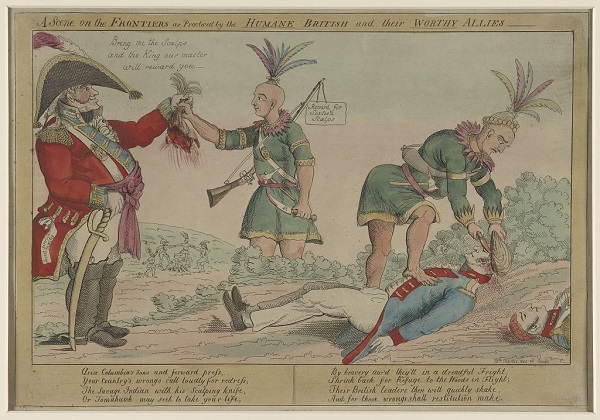

A scene on the frontiers as practiced by the humane British and their worthy allies, illustration past William Charles, published in Philadelphia circa 1812. This cartoon may have been prompted by the August 1812 Native American attack on Fort Dearborn and the buy of American scalps there by British Colonel Proctor.

Equally Troy Bickham points out in his volume, The Weight of Vengeance: The United States, The British Empire and the War of 1812, conflicts between the colonists and the American Indians, whom the British had a long-standing brotherhood with, were zero new in N America and they had never been grounds for war with Britain in the past so it is unlikely they would be in 1812.

Expansionism:

American expansion into British-held Canada is considered withal another cause of the War of 1812. If America could learn Canada, it would non only double its state mass but also banish the American Indian's greatest allies, the British.

Without back up from the British, it would exist difficult for the American Indians to attack American settlers or to cease American settlers from seizing the native's lands in the north and the west, thus allowing for greater American expansion, according to Alastair Sweeney in his book Burn Along the Borderland: Groovy Battles of the War of 1812:

"For many Americans, specially those with their eyes on western holding, 1812 was a war to seize and control vast tracts of land, and kick out the Indian inhabitants. As such it was a form of block busting. In this respect, the War of 1812 was astonishingly successful" (Sweeney 20.)

In addition, there were also a number of financial and strategic military reasons to aggrandize into Canada, according to Taylor:

"Many Republican Congressmen longed to oust the British from the continent and to annex Canada…Expansionists argued that annexing Canada would compensate Americans with land for their commercial losses at body of water and for the military machine cost of invasion. Annexation would likewise deprive the British fleet of a valuable source of timber. Above all, the conquest would sever the British connection to the Indians who blocked American expansion westward." (Taylor 137.)

However, Taylor argues that some historians believe expansion was just a means of waging war, not a reason for starting it:

"Historians have long debated the master crusade of the declaration of war. Early in the twentieth century, they stressed the longing of western politicians to conquer Canada…But subsequent historians discounted the strength of western interests and of the drive to seize Canada. 'The conquest of Canada was primarily a means of waging war, non a reason for starting it,' Reginald Horsman claims. Stressing that the 3 western states had merely x of the House's 142 members, these scholars insist that southern and Pennsylvania Republicans pushed the war and that they had no particular lust for Canada. According to this interpretation, these congressmen primarily reacted confronting the British meddling with American ships on the high seas. Stressing the British Orders In Council, these scholars down-play all other problems, even impressment." (Taylor 134.)

Reginald Horsman argues, in his book The Causes of the War of 1812, that historians frequently quote the speeches of state of war hawks of the fourth dimension, such as Henry Clay, Richard K. Johnson, Peter B. Porter and Felix Grundy, to back up the statement that expansion was a cause of the war yet, if you examine their speeches to Congress in the build up to the war, the dominating theme of these speeches are maritime rights, particularly the right to export American produce without interference.

In addition, not anybody was on board with the idea of conquering Canada at the time. Many politicians felt that acquiring and maintaining such a big amount of state wasn't the all-time idea for America because information technology would be too expensive and hard to manage and might lead to the creation of more than northern states which would threaten the land'due south regional balance of ability.

As a solution, a program was proposed to utilise any newly conquered country "as a bargaining bit in a peace treaty, restoring Canada to Great britain in exchange for maritime concessions." (Taylor 139.)

This idea made the conquest of Canada even less appealing though because many wondered why the government should invest so much time, money and resource into something that they were but going to give away at the end of the war.

Congress fifty-fifty went so far as to vote on a program to create a temporary provisional government in Canada until it could be returned to British rule in a peace treaty simply the bill was defeated, with 16 opposed and 14 in favor.

Even though Americans were uncertain what to do with Canada, they invaded anyway. Without a clear program in place, Canadians were unwelcoming of American troops and viewed them as invaders rather than liberators of British rule, greatly hampering the war endeavour there.

American Sovereignty:

In his volume, The Weight of Vengeance: The Usa, The British Empire and the War of 1812, Troy Bickham argues that the War of 1812 was really almost America asserting its independence from Great Britain once and for all.

Bickham states that the United State'due south long list of grievances against Bully United kingdom in its proclamation of war all boils downward to this one single issue:

"Although each issue was important and merits individual investigation, treating them but equally a checklist misses the larger subject at stake: sovereignty of the United states of america in a postcolonial world…Madison'southward state of war message is a document that aims for consensus – or at least enough understanding to pass a declaration of war – and and then it selects those issues on which a bulk of members of Congress could agree. And those problems all speak to a single theme: equality of the United states among European nations and sovereignty over its own diplomacy…." (Bickham 21)

Bickham goes on to say that the war was not simply nigh British impressment of American sailors or the Purple Navy interfering in American trade with France but was instead about stopping Neat Britain, and other European nations, from believing they could do these things in the get-go place:

"The authorities of the United States and its supporters believed that for too long Britain had directed the Anglo-American relationship, fostering deep-seated resentment for what many believed was Britain's continuing purple mental attitude. Declaring war in June of 1812 was an American try to redefine that relationship and turn the The states into a leading protagonist" (Bickham 21.)

Yet, other historians, such as Sweeney, don't hold and argue that the war was about expansion, not independence:

"Some accept argued that 1812 was the second American Revolutionary War. It was non. It was the first American Expansionary State of war. In the war of independence, France had to step in to save the colonists, a fact that severely rankled the British. Simply in 1812 there was no rich Oncle Louis beyond the seas to transport his navy and regiments of troops to Yorktown. In that location was a rapacious new emperor named Napoleon, whose only real interests were European. In exchange for cash, and for attacking the British in North America while he invaded Russia, Bonaparte donated Florida and Louisiana to his American friends, and gave them a western destiny" (Sweeney 23.)

If American sovereignty was a crusade for war, it'due south not articulate how much of a factor it was since it was never deemed an official cause and was never listed in Madison'south grievances against the British.

To learn more about the State of war of 1812, check out the following article on the Best Books Nearly the State of war of 1812.

Sources:

"War of 1812-1815." Office of the Historian, Agency of Public Affairs, United States Department of State, history.state.gov/milestones/1801-1829/war-of-1812

Bickham, Troy. The Weight of Vengeance: The U.s.a., The British Empire and The War of 1812. Oxford University Press, 2012.

Springer, Paul J. "The Causes of the War of 1812." Foreign Policy Research Institute, 31 March. 2017, www.fpri.org/article/2017/03/causes-war-1812/

Borneman, Walter. 1812: The War That Forged a Nation. Harper Perennial, 2004.

Taylor, Alan. The Civil War of 1812: American Citizens, British Subjects, Irish Rebels, & Indian Allies. Vintage Books, 2010.

"Two Wars for Independence." American Battleground Trust, www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/two-wars-independence

"The War of 1812 Could Have Been the War of Indian Independence." Indian Land Today, 17 May. 2017, newsmaven.io/indiancountrytoday/archive/the-war-of-1812-could-have-been-the-war-of-indian-independence-NgDgX3JKHEaPWtiUIyMxBA/

"Entanglement in World Affairs." The Mariner'south Museum, world wide web.marinersmuseum.org/sites/micro/usnavy/08/08d.htm

Brunsman, Denver. The Evil Necessity: British Naval Impressment in the Eighteenth Century Atlantic World. University of Virginia Press, 2013.

Deeben, John P. "The War of 1812: Stoking the Fires." National Archives, www.athenaeum.gov/publications/prologue/2012/summer/1812-impressment.html

Sweeney, Alastair. Burn down Forth the Frontier: Bang-up Battles of the War of 1812. Dundurn Press, 2012.

Foreman, Amanda. "The British View the War of 1812 Quite Differently Than Americans Do." Smithsonian Magazine, Smithsonian Institute, July. 2014, www.smithsonianmag.com/history/british-view-state of war-1812-quite-differently-americans-do-180951852/

Source: https://historyofmassachusetts.org/war-of-1812-causes/

0 Response to "1. What does the word impressment mean in regards to the War of 1812?"

Post a Comment